Women artists in 1905 were often on the forefront of movements for social change. Mary Ware Dennett used her own personal experiences as an artist, wife, and mother, to advocate for sex education and birth control at a time when such support was considered extremely controversial.

Mary Ware was born in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1874, and moved with her family to Boston after the death of her father. She attended the school of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts from 1891-1893, and took a position as head of the Department of Design and Decoration at the Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry (now Drexel University) when she was 20. After three years there, she and her sister Clara went to Europe to travel and study. They acquired some samples of Cordovan leather hangings, and revived the craft, teaching themselves how to make these pieces. On their return to Boston, they opened a handicrafts store, which later came part of the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts which Mary helped found. Mary continued to serve as the Artistic Director for the shop.

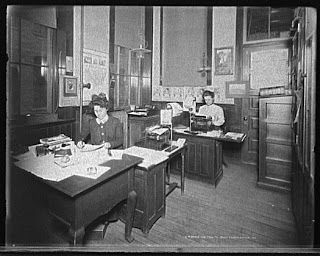

Mary's goal for the SAC was to help garner financial independence for arts and crafts workers. But the board of the SAC was more interested in guiding consumer tastes, and insisted on taking a commission from the artists who sold their work at the store; this made it difficult for them to make a profit.

In January, 1905, Mary would resign from the Society's Governing Council in protest. (Of course, there are two sides to every story, and the Society apparently needed the money. 1905 also marked the year that sales in the store were large enough, at $37,000, to permit the Society to achieve its own financial independence.)

In 1900, Mary married Hartley Dennett, a Boston architect. They seemed to have an ideal partnership--Mary was an established professional at the time of her marriage, and she and Hartley worked together at first--she focused on the interior decoration of the houses her husband designed. But Mary found herself derailed by pregnancy, bearing three children in the first five years of her marriage, one of whom died as an infant. All three deliveries were difficult, and they took a toll on her health. After the birth of her third child in 1905, she suffered serious internal injuries and her doctors advised her to have no more children. But birth control was never discussed. The Dennetts, both in their early 30s, were educated, well-traveled, and progressive. But Mary later wrote: "I was utterly ignorant of the control of conception, as was my husband also. We had never had anything like normal relations, having approximated almost complete abstinence in the endeavor to space our babies."

Mary felt that the only alternative was to give up sex. Hartley was not about to follow suit, and in 1907, whhile Mary was in New York having surgery to repair the damage suffered after her last child, Hartley had an affair with one of his architectural clients.

When Mary discovered this, she determined to end the marriage, and was able to win custody of her two sons in 1909. The Dennetts were granted a divorce in 1913.

Mary had become involved with the woman suffrage movement in 1908, and in 1910 she took a job with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and moved to New York City. After resigning from NAWSA in 1915, she joined Jessie Ashley and Clara Gruening Williams in founding the National Birth Control League (which would become the Voluntary Parenthood League in 1919).

Also in 1915, Mary wrote a pamphlet for her adolescent sons entitled "The Sex Side of Life". It explained reproduction in no-nonsense terms, and represented sex as a vital and joyous part of life. After privately distributing copies to friends and acquaintances for several years she published the pamphlet in 1918. Throughout the 1920s it was widely distributed to individuals, youth and church organizations, and state health departments.

In 1922, the Solicitor of the Post Office banned the pamphlet as obscene, and Mary Ware Dennett was put on trial in 1928 under the

Comstock Law. (This refers to a law enacted by Congress in 1873,

An Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use. Anthony Comstock was the head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, an organization financed by wealthy and influential New Yorkers. He and his organization lobbied hard for the bill, and, after it was enacted into law, Comstock was appointed special agent of the U.S. Post Office and charged with enforcing it, a position he held for 42 years.)

Mary was convicted and fined, but appealed the decision with the backing of the ACLU.

Two years later, the US Circuit Court of Appeals held that the Comstock Law "must not be assumed to have been designed to interfere with serious instruction regarding sex matters." The Dennett case was part of a series of decisions that culminated in a 1936 ruling in

United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries. This decision removed all federal bans on birth control materials and information as tools for medical professionals. However, contraception per se was not removed from the prohibitions of the Comstock Law until 1971.

Interestingly enough, the Comstock Law gave rise to George Bernard Shaw's coinage of the word "comstockery" in 1905, when Comstock attacked Shaw's play,

Mrs. Warren's Profession, as "one of Bernard Shaw's filthy productions" by "this Irish smut dealer." In a letter to the

New York Times on September 26, 1905, Shaw responded: "Comstockery is the world's standing joke at the expense of the United States."

Illustration Credits and References

Illustration Credits and References

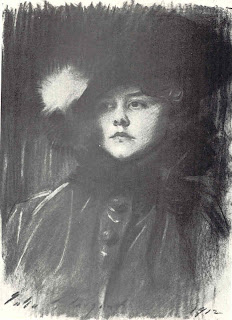

Photo of Mary Ware Dennett from album page in the Carrie Chapman Catt Albums, part of the Carrie Chapman Catt Papers at Bryn Mawr College Library Special Collections, album 5, “New York State and N.Y. City.”

Other sources for this article included:

Harvard University, Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America.

Dennett, Mary Ware, 1872-1947. Papers, 1874-1944: A Finding Aid."Powders, Pills, Pessaries, Pamphlets, and the Post Office: The Struggle for Access to Sex Education and Birth Control,"

News From the Schlesinger Library, Spring 2009.

Christen, Richard S., "Julia Hoffman and the Arts and Crafts Society of Portland: An Aesthetic Response to Industrialization,"

Oregon Historical Quarterly, Volume 109, No. 4, Winter 2008.

Rengel, Marian,

Encyclopedia of Birth Control, Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 2000.

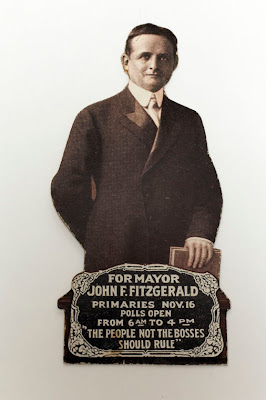

John F. Kennedy's grandfather, John F. "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald, ran for mayor of the city of Boston in 1905. The special election had been precipitated by the sudden death of Mayor Patrick Collins in September. Fitzgerald won the Democratic primary eight weeks later, and then defeated his opponent, the highly respected speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, Louis Frothingham, in the general election.

John F. Kennedy's grandfather, John F. "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald, ran for mayor of the city of Boston in 1905. The special election had been precipitated by the sudden death of Mayor Patrick Collins in September. Fitzgerald won the Democratic primary eight weeks later, and then defeated his opponent, the highly respected speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, Louis Frothingham, in the general election.