By night (and on selected afternoons), Eleonora Sears was a beautiful and popular young society woman in Boston (and New York), frequently mentioned in the "Table Gossip" column in the 1905

Boston Sunday Globe.

But by day she was a talented, energetic, and daring athlete, playing golf, swimming, riding horses, walking great distances, and winning tennis singles, doubles, and mixed doubles championships in Massachusetts and elsewhere.

Her first appearance in "Table Gossip" in 1905, on January 1, noted her presence at a dinner dance in New York over the Christmas holidays, celebrating the debut of President Roosevelt's niece, Corinne Douglas Robinson. She sat at a table presided over by Miss Eleanor Roosevelt (who would go on to marry Franklin later that year), and, according to the

Globe, Miss Sears was "one of the most attractive girls" there.

Eleo had been born in 1881 into a well-to-do Boston family: Thomas Jefferson was her great-great-grandfather and her father was a shipping and real estate tycoon. The Sears lived in a townhouse at 122 Beacon Street, and they were a tennis family. According to the website of the

International Tennis Hall of Fame, her father, Frederick Sears, was one of the first to play tennis in the U.S. in 1874, and her uncle,

Richard Dudley Sears, was the original U.S. champion (winning the first US open in 1881 and every year thereafter through 1887).

Later in 1905, on a rainy Monday in early June, Eleonora wore white dotted French muslin over white silk and a white hat with pale blue plumes, and carried daisies as a member of the wedding party at the union of Grace Dabney and Robert Wrenn at Nahant.

On August 13, 1905, the

Globe reported that she was deferring her visit to Newport as she is “having a very good time in riding, driving, swimming, and tennis with her own friends on the North Shore.” But by August 15, she was playing both singles and doubles at a lawn tennis tournament on the Casino Courts in Newport arranged by Mrs. John Jacob Astor and others. (Mrs. Astor would be divorced from her husband within five years, and therefore would not accompany him on his fatal Titanic journey in 1912.)

By the end of 1905 she was planning a visit to her friend Alice Roosevelt at the White House, and then expected to be off to Europe in early 1906 to visit friends in London.

The fact that Eleo was on full duty in society, attending the weddings, balls, debuts, and other events that were considered

de rigeur for a woman of her day, seemed to give her the license to do what she wanted the rest of the time. She was one of the first women in Boston to learn to drive a car, and was frequently seen driving fast and skillfully around the city. (A 1908

Boston Evening Record tidbit notes that Eleonora Sears and Marie Lee had both "been seen driving through the congested parts of the city with the coolness of experts." Apparently there was some heated discussion among their friends about which of the two was the better driver, and "the champions of Miss Lee wanted to arrange a competition. . . . [T]here may be some wild driving through the city by two very good-looking lovers of the motor shortly.")

Sometime in 1905 or 1906, Eleonora started "being seen with" the young Harold Vanderbilt, heir to the Vanderbilt fortune, who shared many of Eleo's sporting proclivities. (He would go on to take the America's Cup three times in the 1930s.) They denied their engagement for some years (though Eleo's mother announced a "trial engagement" in 1911), and eventually drifted apart.

Eleo would go on to an incredible career as a sportswoman--the first great multi-sport woman of the 20th century. In 1910, when most of her accomplishments were still to come, she was proclaimed in a magazine article as "the best all-around athlete in American society." She would win 240 trophies in a variety of sports during her career.

Eleo continued to play tennis, winning the US women's doubles title with Hazel Hotckhiss Wightman in 1911 and 1915, and again with Molla Bjurstedt in 1916 and 1917. She was a finalist for the women's singles title in 1912, won mixed doubles with Willis Davis in 1916, and would be inducted into the Tennis Hall of Fame in 1968, shortly after her death.

She also continued to walk! She frequently walked from Boston to Providence, with her best time coming in 1926, when she walked the 47-mile trip in 9 hours and 53 minutes. (My father, who was born in 1920, recalls seeing motion picture images of this walk of Eleonora's on a primitive movie player he had as a child.) During a visit to France she walked 42.5 miles from Fontainebleu to the Ritz Bar in Paris in eight and half hours. She once walked the 73 miles from Newport to Boston in 17 hours.

She continued to swim--a 1908

Globe article reported that she would be “glad to accept the swimming race challenge” of Miss Vera Gilbert, the belle of New York’s 400. She was the first (not just first woman) to swim the four and half miles from Bailey's Beach to First Beach in Newport.

She bred and trained show horses for most of her adult life--and rode horses until she died in 1968. She took up polo (a favorite sport of her male society contemporaries), shockingly riding her horse astride. She was the first woman known to have worn trousers for sporting purposes when in 1909 she appeared on the polo ground of the Burlingame (CA) Country Club in breeches and a cutaway coat and asked to be allowed to participate in a match. She was promptly ordered to leave the field. In 1912, when she was seen frequently around Burlingame in her riding breeches (only on "occasions when I had just returned from riding" she claimed), the "Burlingame Mothers' Club" passed a resolution against her behavior. (While this resolution was posted all around town, Eleonora later found out there was no such organization.) Staying the course, she became the first woman to ride astride at the National Horse Show, in 1915.

She started playing squash in 1918, and in 1928 helped to found the US Women's Squash Racquets Association. She was its first singles champion that same year (at the age of 46), later served as its president, and was captain of the US national team.

She also would participate in baseball, field hockey, and auto racing. She would pilot planes, skipper yachts, and race power boats.

And she would continue to play her role in society. In 1924, when he spent a packed day in Boston hunting by day at Myopia, and dancing by night with the debutantes, Prince Edward, the Prince of Wales (although 13 years her junior) was said to be so charmed by her that he spent much of the evening as her dancing partner. (Edward would of course go on to marry Wallis Simpson, and abdicate the British throne.)

Another male admirer wrote a letter to

Time magazine, published on February 22, 1963, which sums up Eleo's dual life:

Sir: I am amazed by the amount of publicity given to the announcement that Attorney General Robert Kennedy and some others managed to walk 50 miles. In December 1925, Miss Eleonora Sears walked from Providence to Boston, a distance of 47.8 miles, in 10 hrs. 20 min.

I know because I walked with her. Miss Sears entertained me for dinner that evening, and I took her to the theater. Miss Sears knows her age better than I do, but she was then in her 40s at least, and could probably outwalk the New Frontiersmen today.

ALBERT P. HINCKLEY, Orlean, Va.

Nothing like a brisk 10 hour walk to get you warmed up for an evening of dining and theatre. Way to go, girl!

Illustration Credits and References

The painting of the young Eleonora (entitled

Young Girl in Rose (or Portrait of Eleonora Randoph Sears)) was painted by

John White Alexander in 1895 when Eleonora was 13; the image appears on the

Art Renewal Center website.

The auto is a current photograph of a 1914 Rolls Royce that was owned and driven by Eleonora (presumably when it was new!)

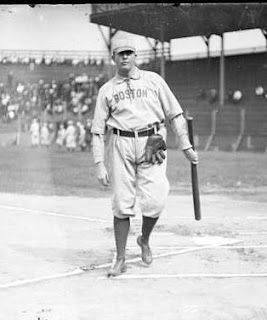

The photograph of Eleonora with her racquet appears on the

Tennis Hall of Fame website.

The information about Eleonora was culled from numerous sources including the

Boston Daily Globe, several other regional US newspapers, the

Tennis Hall of Fame website, the

Hickok Sports website, and many other websites devoted to women and sports.