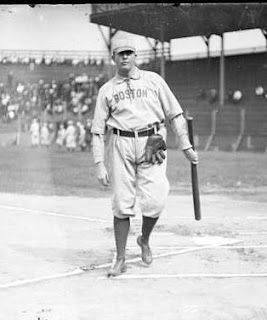

Photo of Fred Lorz in 1906.

Photo of Fred Lorz in 1906. Patriots' Day has been a legal holiday in Massachusetts since 1894. It commemorates the battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, the start of the American Revolution.

Bostonians who are familiar with modern Patriots' Day activities would find a lot to recognize in the holiday celebrations that took place on April 19, 1905. The Lexington fife and drum corps marched over Paul Revere's route; 25,000 spectators were on hand in Concord to view a civic and military parade; and dances, dinners, and athletic events also marked the date.

The 1905 Boston Marathon boasted 78 starters, about half of whom finished the race. (At that time the distance was 25 miles--mostly the same as today's route, finishing at the corner of Boylston and Exeter, near the Boston Public Library, but starting in Ashland instead of neighboring Hopkinton.) The winner was Fred Lorz of New York, in a time of 2:38.25; second place finisher was Louis Marks, also of New York; and third place went to a local man, Robert Fowler, running for the Cambridgeport Gym.

Lorz tripped over his trainer (one of 60 bicyclists accompanying the runners) near the end of the race, but was able to cross the finish line--the next day's

Boston Daily Globe catches the felled bicycle and the falling runner in a terrific action photo.

Many behaviors that characterize the Marathon today were already present in 1905. A media car (the Globe's "White Steamer") led the runners; Wellesley women cheered on the "fellows" as they passed the College; and the huge crowd of men, women, and children near the finish line (most of whom who had waited in place for an hour and a half) shouted for every runner and "there was no let-up [in cheering],even after the first few had plodded in".

1905 was also the first year in which George V. Brown fired the starter's pistol at the beginning of the race. (Brown would go on to serve as starter until 1937, and his descendants are still honored with the responsibility.)

There were also a few differences! A Dr. Blake, who was examining the runners at the end of the race, noted that most men were in pretty good shape, but that those who had

not drunk whiskey along the route "fared better".

Race winner Fred Lorz had achieved some negative press the year before when he participated in the 1904 Olympic marathon, run in conjunction with the St. Louis World's Fair. After suffering an injury at the nine-mile mark, he rode in a car for 11 miles; when the car broke down, he ran the rest of the way to the finish and was originally hailed as the winner. (See Rosie Ruiz!) After being tossed out of membership in the AAU, he was later reinstated when it was determined that he did not intend to defraud, and had merely thought to play a practical joke. After winning the Boston race in 1905, Lorz, who actually seems to be not much of a joker-type (given the pompousness of the quote which follows and the expression on his face in the photo above) referenced his history: "I guess those people who said I tried to steal the St. Louis race will now do a little thinking. . . I never claimed to have won the Olympic race, and after I finished I told Sec. James E. Sullivan of the AAU that I rode in that automobile."

Third place finisher Fowler would also be involved in another interesting race, when he participated in the running of the Empire City Marathon in Yonkers, NY on January 1, 1909, a bitterly cold day. Fowler won that race, setting a world record that lasted for about six weeks, but the race was declared over after the first seven men crossed the finish line. The

New York Times surmised in their story lead that "the incompetency of the Yonkers police" was responsible for the premature finish. The Yonkers police chief, who was responsible for keeping order, rode a horse up and down the track; scorers and officials were interfered with by a boisterous crowd of 10,000; and three mounted police "rode through the group of scorers repeatedly". When an official complained, Chief Wolff "merely smiled and drove his horse at the officials, scattering them left and right."

In addition, the

Times observed that the "contest in several respects savored of a farce. One contestant smoked a pipe while running around the track, another essayed a theatrical faint in front of the judges."

Police behavior seems to have been much more appropriate at the Boston race in 1905. Approximately 70 city policemen were on duty to control the crowd (estimated at over 75,000 between Coolidge Corner and the finish of the race). The

Globe observed that these officers "did their work well, gave no offence, and left the scene with every spectator feeling that the police are humane and capable."

Fowler would go on to savor a win in the Boston Marathon in 1909, only a few months after the Yonkers farce. Frederick Lorz would finish second that year.

Illustration Credits and ReferencesPhoto of Fred Lorz above from the

Chicago Daily News negatives collection, DN-0003451. Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society.

Click here to read more about the bizarre 1904 Olympic marathon. (Lorz's deception is only part of the story!)

Click here to see a short article, accompanied by a WBZ-TV video, about George V. Brown, race starter, whose bronze statue was unveiled at the running of the 2008 marathon.